Housing Affordability for Sydney Students - It's a Nightmare

Three-quarters of university students know saving a house deposit won't be easy, yet most still expect to buy within 10 years, a gap between hope and housing economics that reveals just how broken Australia's property market has become.

This article was originally submitted as part of a postgraduate degree and follows academic referencing conventions.

Growing wealth inequality in Australia is largely a result of rising housing prices and thus increasing the property wealth of older generations (Ball, 2018). These higher housing prices have prevented a significant segment of younger people from accessing home ownership (Simon and Stone, 2017). Price rises driven by historically low interest rates, favourable tax incentives and strong levels of migration have led to housing affordability issues for first home buyers (Committee for Economic Development of Australia, 2017) and concerns for students aspiring to future home ownership (GEOP6070, 2020).

This report outlines the disparity between student expectations for their future housing and the reality of purchasing a first home in Sydney without financial assistance from family or friends. Policies aimed at returning housing price growth to sustainable and affordable levels as well as initiatives to enable first home buyers to enter into home ownership are discussed. Shelter NSW can advocate for these policy interventions to address the issue of housing affordability and improve outcomes for current students and younger generations.

Housing Experiences of University Students

A recent survey of Macquarie University students shows that 69% of students in the 18 to 29 age group are currently living with family or a partner with 85% of those living rent-free (GEOP6070, 2020). This is higher than the general young adult population with 56.4% of men and 53.9% of women in this age group living in the parental home, however, this data does not include those living with a partner (Wilkins et al., 2019). Fifty-two per cent of students living in private rental accommodation or share households are in rental stress, meaning they spend 30% or more of their income on rent and, significantly, 25% of students renting directly from a landlord or real estate agent are spending 50% or more of their income on rent (GEOP6070, 2020).

A further issue for students surrounds the stability of housing tenure with 50% of survey respondents agreeing that fear of eviction from rental properties is a concern and students in a focus group cite instability as a reason for wanting to move into home ownership (GEOP6070, 2020). This concern was shared in a recent survey of young Australians where 72% rated finding a secure home a priority (Parkinson et al., 2019).

Housing Expectations of University Students

Although the majority of students surveyed agreed it will not be easy to purchase their first property (77%) or save a deposit (75%), 81% believe it is likely they will eventually purchase a property and 61% believe it is likely they will purchase a property within the next 10 years (GEOP6070, 2020). The ability to meet these expectations will depend on their income after graduating, the capacity to save a 20% deposit and transfer costs, the potential to service a mortgage and future housing prices.

Home Purchase: Servicing a Mortgage

The median weekly earnings for a university graduate with a bachelor’s degree or higher is $1,403.80 per week (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], 2019), while the median house price in Sydney is $925,000 (ABS, 2020a). Assuming a savings rate of 20% of gross earnings, invested monthly at the current savings account interest rate of 1.35% (Macquarie Bank, 2020), it would take approximately 11 years and 9 months to save a deposit of $185,000.

However, as purchasing a first home is often related to entering into married and de facto relationships (Simon and Stone, 2017) and the majority of couples are dual-earner (Wilkins et al., 2019), a couple could save a deposit for a median priced property in approximately 6 years. These calculations assume housing prices remain constant during the saving period, however, if they were to increase at a rate of 7% per year, then it would take almost 12 years for a dual-earner couple to save a 20% deposit.

With regards to loan serviceability, principal and interest repayments on a 30-year mortgage of $740,000 at an interest rate of 2.64% would be $2,988 per month (Moneysmart, 2020). This repayment equates to 25% of monthly earnings and therefore would not place the couple under mortgage stress.

Home Purchase: Saving a Deposit

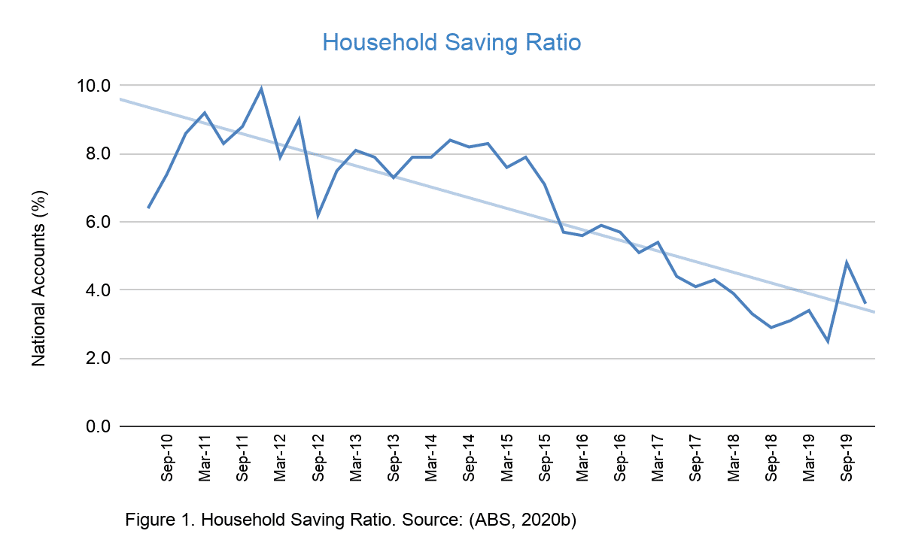

As servicing a mortgage is unlikely to be an issue, the greater concern is the ability to save a deposit considering the potentially unrealistic assumption of a 20% savings rate. Prior to COVID-19, the household saving ratio was trending downwards (Figure 1), with the rate in December 2019 being 3.6% of post-tax income (ABS, 2020b). At this rate, a dual-earner couple would save $346.56 per month and take almost 35 years to save $185,000, although it is worth noting this ratio is an aggregate of all households and influenced by various factors (Reserve Bank of Australia, 2016).

A household's capacity to save a deposit is increasingly a barrier to home ownership, especially in cases where the rent exceeds 30% of household income (Maclennan and Long, 2020). Wood et al (2006) also state the deposit requirement for borrowing is delaying access to home ownership and that the capacity to save a deposit is more of a concern than the ability to service a loan. This deposit gap is sometimes filled by financial assistance from parents (Yates, 2017) although only 48% of students surveyed expect to receive assistance from family to purchase a property (GEOP6070, 2020).

Nevertheless, student expectations of purchasing property may be realised as tertiary-educated households who are employed full-time have higher potential lifetime income and are more likely to become home owners (Simon and Stone, 2017).

Recommended Policy Interventions

Tackling housing affordability requires a multi-level governmental approach to address the drivers of rapid housing price growth, bridge the deposit gap for first home buyers, resolve the issue of rental insecurity facing long-term renters and consider initiatives to enhance liveability in Sydney.

Housing tax reform designed to reduce speculative property investing involves reducing or phasing out negative gearing and capital gains tax concessions (Pawson et al., 2015). Limiting negative gearing and reducing the capital gains tax discount would reduce housing market volatility, improve affordability and increase government tax revenue (Daley and Wood, 2016).

Stamp duty reform is also required as this transaction cost discourages mobility for owner-occupiers and could be replaced with a more equitable and efficient land tax (Pawson, Milligan and Yates, 2020). Replacing stamp duty with land tax also promotes economic growth leading to increases in state tax revenue (NSW Productivity Commission, 2020) which can be used to address affordable housing issues.

The difficulty of saving a deposit can be addressed by implementing deposit schemes or shared ownership options managed by community or financial institutions and guaranteed by the state government (Pinnegar et al., 2010). The state government can also investigate schemes to assist young adults who do not have access to financial assistance from family, expand low deposit programs for first home buyers and facilitate efforts to raise financial literacy and knowledge regarding housing and consumer rights (Parkinson et al., 2019).

With more Australians renting long-term, either out of necessity or choice, stronger tenant protections need to be put in place allowing for longer term leases, longer notice periods, restrictions on evictions and legislated limits on rent increases (Shaw, 2014). The state government should consider reforms to tenancy laws and regulations to support the objective of improving security and tenant rights.

An additional solution is to enhance the appeal and liveability of less expensive suburbs. Forty-five per cent of students surveyed would ideally like to purchase a property in the Lower North Shore, the Northern Beaches or the Eastern Suburbs of Sydney (GEOP6070, 2020). Issues of liveability can be addressed by local government in collaboration with the state government to attract home ownership outside of these more expensive established areas. Improving social and transport infrastructure, access to education, health resources and employment opportunities would improve the liveability of more affordable locations (Greater Sydney Commission, 2018).

Conclusions

A large number of students are choosing to live in the family home while at university whereas those who are living in private rentals and share accommodation often face financial pressure associated with rental stress. The majority expect to enter into home ownership within ten years but without government policy intervention this may not be possible due to increasing housing prices and difficulty in saving a deposit.

Addressing wealth inequality resulting from rapid rises in property values should be a priority for all levels of government. Although a reduction in tax concessions would likely have an impact on reducing or stabilising housing prices and thus affordability, current government policy does not support these reforms and there has been no indication of an intention to modify relevant policies. While advocating for policy reform at the federal level is important, Shelter NSW may prefer to take a more pragmatic approach by focusing its advocacy efforts on state and local government policy interventions.

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2019. Characteristics of Employment, Australia. cat. no. 6333.0. Table 5.1 Distribution of weekly earnings for employees by educational qualification. August. Canberra: ABS.

Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2020a. Residential Property Price Indexes: Eight Capital Cities. cat. no. 6416.0 Tables 4 and 5. Median Price (unstratified) and Number of Transfers (Capital City and Rest of State). June. Canberra: ABS.

Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2020b. Household Income Experience.

Ball, J., 2018. Overview. In: How unequal? Insights on inequality. Committee for Economic Development of Australia, p.25.

Committee for Economic Development of Australia, 2017. Housing Australia.

Daley, J. and Wood, D., 2016. Hot property: Negative gearing and capital gains tax reform. Grattan Institute.

GEOP2070/6070, 2020. Student Housing Experiences and Expectations.

Greater Sydney Commission, 2018. Greater Sydney Region Plan: A Metropolis of Three Cities. Sydney: NSW Government, pp.68-72.

Maclennan, D. and Long, J., 2020. Extending Economic Cases for Housing Policies: Rents, Ownership and Assets. City Futures Research Centre, pp.5-8.

Macquarie Bank, 2020. Everyday Banking Savings Account.

Moneysmart, 2020. Mortgage Calculator.

NSW Productivity Commission, 2020. Productivity Commission Green Paper: Continuing the productivity conversation. NSW Treasury, p.260.

Parkinson, S., Rowley, S., Stone, W., James, A., Spinney, A. and Reynolds, M., 2019. Young Australians and the housing aspirations gap. AHURI Final Report No. 318. Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited, pp.4, 95-96.

Pawson, H., Milligan, V. and Yates, J., 2020. Housing Policy in Australia: A Case for System Reform. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan, p.304.

Pawson, H., Randolph, B., Yates, J., Darcy, M., Gurran, N., Phibbs, P. and Milligan, V., 2015. Tackling housing unaffordability: a 10-point national plan. The Conversation.

Pinnegar, S., Milligan, V., Randolph, B., Quintal, D., Easthope, H., Williams, P. and Yates, J., 2010. How can shared equity schemes work to facilitate home ownership in Australia? AHURI Research and Policy Bulletin No. 124. Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited.

Reserve Bank of Australia, 2016. The Household Saving Ratio.

Shaw, K., 2014. Renting for life? Housing shift requires rethink of renters’ rights. The Conversation.

Simon, J. and Stone, T., 2017. The Property Ladder after the Financial Crisis: The First Step is a Stretch but Those Who Make It Are Doing OK. Reserve Bank of Australia, pp.5-10.

Comments